Over the years, as an analyst, advisor and even as an entrepreneur, I’ve heard the phrase “Our strategy is to disrupt

Over the years, as an analyst, advisor and even as an entrepreneur, I’ve heard the phrase “Our strategy is to disrupt

Why? I’ve always believed that the fastest way to success is to avoid trying to knock somebody off the ladder and, instead, build your own ladder. You control your future. You shape the market. You let the people on the other ladder pursue their evolutionary strategies while you quietly create a revolutionary strategy.

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN DISRUPTION AND INNOVATION

To be clear, there is a definite relationship between “disruption” and “innovation” not to be confused with Clay Christensen’s “Disruptive Innovation”. Often, they feed off of each other – one leading to the other (or at least providing an opportunity for the other to take hold).

Innovations within a market can ultimately lead to the disruption (or devastation) of an existing or adjacent (but different) market (example: iPhone’s App store devastating video games, wrist watches, cameras). Note that true innovations don’t just offer better versions of existing products, but offer better alternatives to existing products – they ultimately replace them.

Similarly, disruptions within a market (or a vendor if they dominate that market) can often provide an enhanced opportunity for new and innovative vendors and products. The more disruptive a market has become, the greater the opportunity for innovation to create a new, better alternative market. But there are differences.

And far from being singular events, disruptions and innovations can often be associated with long-term evolutionary trends, rather than singular events (Pervasive Communications is a great example of two trends (technology and human behavior) leading to a disruption of both social structures, technologies and global markets (check out Alan Berkson’s framing of Pervasive Communications and a video chat with Brian Reich on the global implications of Pervasive Communications).

DISRUPTION

Disruption, like the stuff that hits the fans, often just happens. It can be caused by any number of different conditions. Disruptions to supply chains. Technological advances. Corporate mismanagement. Natural disasters. All can result in a market (and its vendors) being disrupted. In the extreme, the disruption devolves into a state of chaos – and chaos (while it may offer opportunity for those able to restore order) is usually not a characteristic of a market you want to enter.

To this last point, the notion of “disrupting” a market of a vendor to gain a competitive advantage is more often than not simply the wrong approach (a great example being the often asked question in the analytical/advisory space: “Why hasn’t anybody been able to disrupt Gartner’s business model”). To disrupt an entrenched vendor’s business model means to disrupt their market, which may be extremely difficult/impossible to achieve without disrupting your own chances of stepping in to take advantage of the opportunity (an issue we’ll discuss in Part II).

INNOVATION

Innovation, on the other hand, is more often the result of a “spark” or idea that transcends the products, services and strategies of an existing vendor or market. It creates something new: its own ladder. Rather than competing head to head against an existing market or vendor, it offers an alternative that, if done correctly, is often unnoticed by other vendors. It doesn’t (initially) compete for the same budget, nor does it require a “magic quadrant” or an “us vs them” comparison.

A true innovation stands alone – it is its own product and market replacing the need for existing products and markets. It obsoletes prior structures (an issue we’ll discuss in Part III) and represents – in both the short- and long-term – a new market opportunity.

While a new innovation may ultimately compete for overall corporate/consumer dollars, it is often differentiated enough that it can initially sit along-side existing products and simply blend into the landscape. In fact, the best innovations are the ones that existing market players don’t deem as viable – very different from a product evolution that may be considered cannibalistic if they were to implement it themselves.

Taking it deeper, a true innovation will ultimately replace the need for existing products, vendors and even markets. All though not common, the “existing products” *may* not actually exist (although the need for them may – the case of the impractical market), or if they do exist, they *may* under-perform or not currently meet market demand (something that may not be obvious or intuitive to either consumers or vendors).

Take, for example, the iPhone (introduced only five years ago in 2007). In and of itself, it wasn’t a true innovative product, but rather an evolutionary extension of existing multi-media phones (like the Blackberry). But the Apple App Store – when combined with the iPhone (in 2008) – was a true innovation. It created a new market, obsoleted others and forever changed the way that hundreds of different products (as applications) were brought to market.

MOVING FORWARD

In the next few posts we’ll discuss the different types of disruptions and innovations that commonly occur, and the risks and rewards that accompany each (here’s a thought to ponder: most disruptions – especially man-made – offer more risk than reward, while most innovations offer tremendous reward with very little risk).

Have a different perspective? Toss it out. There are plenty of opinions on this subject and I’m looking forward to the debate.

“Oops!” Broken Lightbulb photo courtesy of Kyle May licensed under Creative Commons

Note: Post updated to highlight and clarify distinction between “disruption and innovation” and “Disruptive Innovation”

It’s hard to think of any aspect of any market sector that doesn’t involve, or revolve around, influence. Back on October 7th, Steve Loudermilk (@loudyoutloud) and I tried a novel approach to our Analyst Relations/Influence chat (#ARchat) by engaging in a joint chat session with #B2Bchat, the B2B chat hosted by Ksenia Coffman (@kseniacoffman), Jeremy Victor (@jeremyvictor), Andrew Spoeth (@andrewspoeth) & the crew at @b2bento.

It’s hard to think of any aspect of any market sector that doesn’t involve, or revolve around, influence. Back on October 7th, Steve Loudermilk (@loudyoutloud) and I tried a novel approach to our Analyst Relations/Influence chat (#ARchat) by engaging in a joint chat session with #B2Bchat, the B2B chat hosted by Ksenia Coffman (@kseniacoffman), Jeremy Victor (@jeremyvictor), Andrew Spoeth (@andrewspoeth) & the crew at @b2bento.

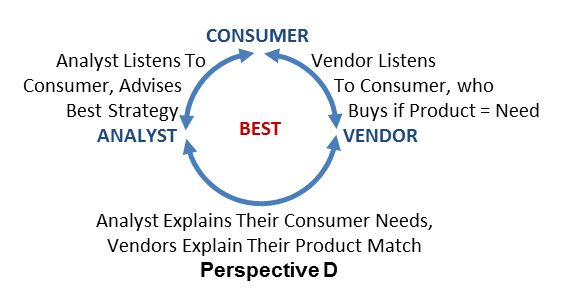

In this way, the best possible product offerings can be designed and deployed, giving each of the three participants what they need – the best value for their dollar spent. Note too that in Perspective D I have placed the Consumer at the top of the circle, since they ultimately control what is purchased, and their needs and requirements should be what ultimately influences the market.

In this way, the best possible product offerings can be designed and deployed, giving each of the three participants what they need – the best value for their dollar spent. Note too that in Perspective D I have placed the Consumer at the top of the circle, since they ultimately control what is purchased, and their needs and requirements should be what ultimately influences the market.