Is it possible to have a Klout Score of Zero (K = 0)?

Is it possible to have a Klout Score of Zero (K = 0)?

Why, you might ask, would anybody want to have such a score in the gamified realm of influence measurement, where higher scores indicate a higher level of perceived online influence?

The answer may lie in the way that Klout profiles you, branding you a Specialist, an Observer, or a Broadcaster. The answer may also lie in how people relate to Big Data, vaguely defined ranking algorithms, and the increased tendency of offline organizations to make some big, and potentially misleading, assumptions about the role of online influence in an offline world.

“Klout calculates billions of data points across over 100 million influencers every day.” ~ Klout.com

Whatever the reason, there are people who simply want out. But opting out, and driving your score to a meaningless Zero, is apparently a bit more difficult in the Klout dimension than one might imagine.

I PRESENT TO YOU MR. SAM FIORELLA

Mr. Fiorella was recently referenced in a Wired.com article (What your Klout Score really means) that delved into an experience he had a while back with a potential employer, who eliminated Sam (and possibly others) from the list of candidates based on his perceived “sub-par” Klout Score. As listed on the Klout.com website…

It’s not the first time something in the online world has impacted a decision in the offline world, and it definitely won’t be the last (see Jeremiah Owyang’s post “How ‘Social Profiling’ Will Work In The Real World“).

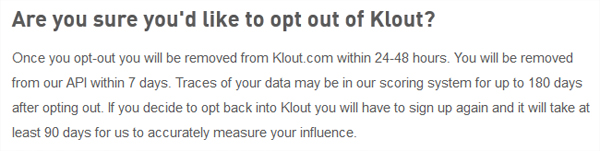

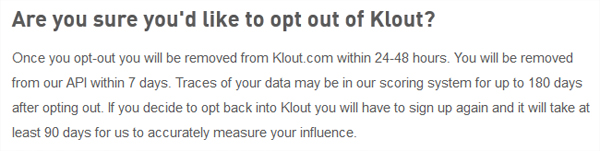

Sam ultimately did improve his Klout Score (into the 70’s) but was never happy with the idea of being ranked (or branded) by an algorithm for online OR offline purposes. So when Klout offered an “opt out” option at the beginning of November, 2011, he promptly did just that. He opted out and initiated the deletion of his Klout profile, per the language on the Klout site:

As far as Sam was concerned, he was satisfied that after opting out nobody would be able to view his Klout Score moving forward and that only trace data would remain in the system (for 180 days, after which it would be removed).

He also understood that Klout would continue track his activities on the public broadcast social site Twitter.

Note: I wouldn’t be surprised if Klout NEEDS to track Sam privately in order to accurately determine the Klout Scores of others within his Twitter social graph. In essence, influencers who are not tracked become dark matter, or invisible thought leaders. They mess with what we perceive by influencing behavior in unseen ways.

But there was also a level of expectation that the information gathered on Twitter (and his resulting private Klout Score) would to be kept private and OFF the Klout.com site.

Unfortunately, it didn’t work out that way.

I PRESENT TO YOU MR. SAM FIORELLA’S GHOST

In the name of full disclosure, I know Sam personally and I am a registered Klout user. I was also aware when he, and others, opted out of Klout last year. So when I read the Wired article, and the various other articles and posts that it spawned, the analyst in me was just a bit curious to see if Sam had in fact been removed from the site. So I search Klout.com and found no public profile or information on him.

But I did come across the profile of a friend of mine, and attached to that profile, in their Influencers list, was the smiling face of Sam Fiorella. On the site, exactly where it should not have been.

Apparently, the phrase “you will be removed from Klout.com within 24-48 hours” – as mentioned in the Klout opt out statement – may not mean what you think it means.

Sam opted out from Klout almost 6 months ago. Could this possibly be the “trace data” mentioned in the Klout “opt out” statement? I don’t believe so, as his current Twitter avatar is on display along with an assumingly current Klout Score of 52 (which sounds plausible since Klout appears to be pulling his data only from Twitter, not the complete list of social sites that Sam previously had linked to his Klout account, and it increased to 53 last night).

But wait, there’s more (thank you Ron Popeil). While I did pass on the option to invite Sam back to Klout (he wouldn’t have accepted anyway), I couldn’t resist the chance to test the software and see if it would allow me to give him a +K in Blogging. It did:

I’m not sure the +K stuck (even though it does now show me a greyed out +K button for Sam and Blogging, it apparently didn’t decrement my +K counter).

I’m not sure the +K stuck (even though it does now show me a greyed out +K button for Sam and Blogging, it apparently didn’t decrement my +K counter).

But the mere fact that it allowed me to go through the action, give me a success notification and offer the option to Tweet the +K out, was more than just a bit interesting – it was a challenge to figure out what had gone wrong, how it might be corrected and to think strategically a bit about some of the larger (beyond Klout) implications it might have.

FOR YOUR CONSIDERATION

From a social perspective, you cannot deny that influence exists – marketing, advertising and sales people have been trying to identify and target influential consumers for years. Nor can we deny that our online and offline lives are colliding extremely fast, and influence in one medium can, and will, transcend to another.

From an online influence measurement perspective, there is a defined need to look for insights in online behavior (served by Klout and other firms such as PeerIndex, Twitalyzer, TweetLevel, etc.), and the people at Klout have been very honest and open with me, and others, about how and why they are undertaking this task.

But there is a disconnect when a phrase like “removed” appears to mean “erased a bit” – not quite how I would interpret it.

CAN WE ACHIEVE ZERO?

When Sam opted out of Klout, he assumed that he would still have a Klout Score, but that his information would no longer be shared or visible to others – in essence giving him a public null Klout Score (K = 0) that he sought. While the data would still exist, and be interpreted by Klout, they would not share their interpretations with others.

So why is Sam Fiorella still appearing on Klout? Perhaps there is an issue that weaves around Klout’s interpretation of words, and the managing of expectations from a contractual Terms of Service (TOS) perspective. Or perhaps it has to do with the massive amounts of Big Data that we are crunching on an ongoing basis, with technology evolving at such a rapid pace that glitches and ghosts, while unacceptable, are going to occur. Either way, there is a flaw somewhere in the system, and Mr. Fiorella has become its poster child.

PRIVACY AND PERVASIVE COMMUNICATIONS

Sam’s issue with Klout is bigger than either Sam or Klout. Not to diminish what Sam is going through, neither Sam nor Klout are alone in facing issues regarding personal data, big data, privacy or changing technology. If anything, his dilemma is indicative of a much larger series of questions and issues that we face.

We live in an age of technology-enabled Pervasive Communications. Our ability to communicate with almost anyone, anywhere at any time, over a multitude of communications channels, is allowing us to unleash our DNA-driven need to create, share and consume content and information with others.

As we do this, our public actions are increasingly tracked, tagged, shared and mined by people and companies that we’ve never met. They’re sifting through piles of Big Data looking for patterns, for trends, for clues regarding what influences our decisions, and how our decisions influence – if at all – the decisions of others. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing, but when this activity lacks true transparency of both intent and use, the user is increasingly, and unknowingly, giving away far more than they are receiving in return.

“There is nothing in the dark that isn’t there when the lights are on.”

~ Rod Serling

The data is out there and it’s not going away. It may lose some of its relevance, but it will still be out there and is increasingly being linked with other data to create “new” data. The questions of who really owns our data (both pre and post-processing), how and when it can be shared and reused, and how much light (transparency) should be shined upon it, will likely be argued (and should be) for many years to come.

While many individuals may argue that they want their data out there (in an effort to achieve a richer, more engaging online experience), I do believe that there are different times and places for private and public, and, as individuals, businesses and governments, we need to continually ask ourselves:

- What should the ground-rules be for how Terms of Service and ownership of data are defined?

- How will we let these definitions and rules evolve and adapt to technology and human behavior patterns that don’t yet exist or have yet to be defined?

- How can we provide true transparency (in simple terms) to online users regarding their data and its linkages with other data (there’s a business out there if you can create that infograph, BTW)? And,

- How we are going play together in an ever shrinking sandbox where transparency has become a buzz-word and personal privacy continues to become increasingly elusive?

I also believe that when an “opt out” option is offered, as it was with Klout, it should be just that – a way for you to take yourself, and your data, OUT of the system. If not for your actions, the data wouldn’t exist in the first place.

Note: Images adapted from Klout.com

I’m going to get right to the point. Platforms don’t define communities, communities define platforms. And when platforms try to define a community, they almost always alienate the community, which, in turn, finds another venue on which to communicate. Simple? Yes. But, unfortunately, most social media “platforms” have yet to grasp this concept.

I’m going to get right to the point. Platforms don’t define communities, communities define platforms. And when platforms try to define a community, they almost always alienate the community, which, in turn, finds another venue on which to communicate. Simple? Yes. But, unfortunately, most social media “platforms” have yet to grasp this concept.

Obamacare, SCOTUS and the Online Veto Button: We all know the power of the “veto” – the ability to simply over-rule all others and say “no” to a particular situation. We see it in many aspects of our lives, from the

Obamacare, SCOTUS and the Online Veto Button: We all know the power of the “veto” – the ability to simply over-rule all others and say “no” to a particular situation. We see it in many aspects of our lives, from the

I’ve always been fascinated by crowds — how they form, why they form, what influences them, and what, in turn, they have the ability to influence. I’ve also always tried to differentiate between crowds and communities, the latter being a more “refined” version of a crowd. Communities have purpose, and common bonds that bind the individuals together. So when I came across a couple of choice documentaries recently, that explored the nature, and science, of crowd/community behavior (and what it means as an individual within a crowd or community) the questions started flying. Fast.

I’ve always been fascinated by crowds — how they form, why they form, what influences them, and what, in turn, they have the ability to influence. I’ve also always tried to differentiate between crowds and communities, the latter being a more “refined” version of a crowd. Communities have purpose, and common bonds that bind the individuals together. So when I came across a couple of choice documentaries recently, that explored the nature, and science, of crowd/community behavior (and what it means as an individual within a crowd or community) the questions started flying. Fast.

Is it possible to have a Klout Score of Zero (K = 0)?

Is it possible to have a Klout Score of Zero (K = 0)?

Over the years, as an analyst, advisor and even as an entrepreneur, I’ve heard the phrase “Our strategy is to disrupt

Over the years, as an analyst, advisor and even as an entrepreneur, I’ve heard the phrase “Our strategy is to disrupt

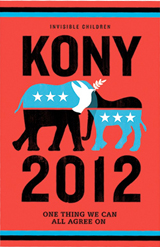

When you craft a message, you generally have a target, or audience, in mind. You probably also have an agenda, or goal, that you wish to achieve, such as awareness, education or a call to action. And both the message and the agenda are typically driven by both your own ideas and those embraced by your target audience. Your message must match your audience, or it’s difficult for them to embrace it.

When you craft a message, you generally have a target, or audience, in mind. You probably also have an agenda, or goal, that you wish to achieve, such as awareness, education or a call to action. And both the message and the agenda are typically driven by both your own ideas and those embraced by your target audience. Your message must match your audience, or it’s difficult for them to embrace it.

Earlier this week, my good friend

Earlier this week, my good friend