[Originally posted on 12Most.com] We live in a world where competition is part of the fabric of life. Survival of the fittest, and all that stuff. The business world is no different. Being about to not only know your competition, but to outsmart them, is just another aspect of the game.

[Originally posted on 12Most.com] We live in a world where competition is part of the fabric of life. Survival of the fittest, and all that stuff. The business world is no different. Being about to not only know your competition, but to outsmart them, is just another aspect of the game.

Here are some relatively basic steps you can take to win the competition game. Are they a bit difficult to pull off? Some of them. But if you can get your hands around even a few, you’ll find yourself in a better competitive position:

1. Know yourself better than anybody else

If you really want to evaluate your competition, you have to first understand what YOU have to offer. This will help you define WHO your competition is. If you do this right — and look at your core competencies, you might find that your ultimate competition isn’t exactly who you think it is.

2. Execute your business first

Going back to point 1, if your business isn’t being executed to its fullest, you may like to think that you are competing against top-tier companies, but the reality is that you may be competing against the middle of the pack, and trying to best “the best” is simply never going to work.

3. Listen to their financial calls

You’d be amazed at the information that comes out of financial calls from public companies. And no, you don’t need to be a financial analyst to participate. Sure, you can read about their call the next day, but short of being in the room with them, listening can give you a sense of excitement or tension that you might not get in print.

4. Read voraciously

From public SEC filings to blogs to articles (and even support forums), the amount of information out there that can prove valuable is immense. How are they perceived? What are their customers openly complaining about? Where is YOUR opportunity?

5. Talk to their customers

If you are not talking to your competition’s customers, you might as well pretend you’re in a business that has no competition. Not only can you gain a good bit of information about your competition, but also about their sales cycles, new products that have been promised — even who their sales reps are (rep churn is very valuable information). Who knows, you may even land a customer yourself.

6. Follow their customers on social media

Customers say the most amazing things on social media. Sure, some of it may be slightly anonymous, or a bit questionable. But when you see a trend of #FAIL hashtags at the end of messages about a competitor’s new product, it’s probably worth looking into. And please, don’t just stop there. Some clever searching can reveal a great bit of information about former customers as well (and open up new prospects at the same time).

7. Talk to (or follow) their suppliers

By our very nature, we tend to look forward — to be customer focused. But what about the people supplying product to your competitors? Did they have a good quarter? Did they have a bad quarter? Could it be that their shipment levels (or margins) are tied to your competitor? Absolutely.

8. Follow their employees on social media

Gaining insight into customer sentiment is incredibly valuable. But gaining insight in employee sentiment is even better. When a social media user’s profile states “I work for XYZ Corp, but my posts are my own”, remember that is usually not the case. People talk, and they talk about work. How busy they are, how late they had to stay at work, how high/low their job satisfaction level is… get my point?

9. Visit Q&A sites

With sites like Focus.com, Quora.com, G+ (no, not the Google version) and LinkedIn Answers, it is becoming increasingly easy to find out what questions users are asking about your competitors products, and the type of responses they are getting to their questions. Are they asking about how to configure a product (perhaps a sign of poor technical support)? Are they asking for alternative products (displeasure with their existing product)? Or are they asking the best places to buy a competitor’s product (a sign of positive sentiment)?

10. Listen to their corporate or customer support social feeds

You’d be surprised how much information you can gather my monitoring a company’s “support” feed on Twitter or Facebook (and soon Google+). Sure, they try to move the customer support issues offline as quickly as possible, but there is still enough activity to gain some insight (and social media is fast becoming a way to quickly spot trends in advance of mainstream awareness).

11. Understand their/your market

In a world where change is now measured in days or months, not years or decades, keeping apace of emerging market trends is just as important as understanding your competition and their products/services. Learn to anticipate what changes will disrupt their (or potentially your) business and be aggressive/proactive. Don’t let them dictate your move, rather seek to influence theirs!

12. Buy one of their products

Unless you are talking about a product made from unobtainium (or a service), it is probably worth getting your hands on one of their products. Buy it used. Buy it damaged. Just get it, and figure out how it works and what it is really capable of performing. You’d be surprised how often that slick-looking data sheet doesn’t quite match up to the real deal. And even if the product is a year old, it can still yield some interesting insights into their design process. To be fair, I’m not advocating you break or even bend any laws or copy any intellectual property (be very careful here – designers should be locked in a different room!). But nothing beats actually having something in front of you to figure out how it works and how you can sell against it.

So there you have it — just a few ways that you can get a leg up on your competition. But remember, it all starts with items 1 and 2 — getting your house in order first.

Featured image courtesy of claudiaveja via Creative Commons.

Being social takes work.

Being social takes work.

I’m going to get right to the point. Platforms don’t define communities, communities define platforms. And when platforms try to define a community, they almost always alienate the community, which, in turn, finds another venue on which to communicate. Simple? Yes. But, unfortunately, most social media “platforms” have yet to grasp this concept.

I’m going to get right to the point. Platforms don’t define communities, communities define platforms. And when platforms try to define a community, they almost always alienate the community, which, in turn, finds another venue on which to communicate. Simple? Yes. But, unfortunately, most social media “platforms” have yet to grasp this concept.

Obamacare, SCOTUS and the Online Veto Button: We all know the power of the “veto” – the ability to simply over-rule all others and say “no” to a particular situation. We see it in many aspects of our lives, from the

Obamacare, SCOTUS and the Online Veto Button: We all know the power of the “veto” – the ability to simply over-rule all others and say “no” to a particular situation. We see it in many aspects of our lives, from the

I recently had the pleasure of speaking at the #140MTL State of Now conference, on May 15th, 2012, in Montreal, Quebec. It was a fantastic event, with some

I recently had the pleasure of speaking at the #140MTL State of Now conference, on May 15th, 2012, in Montreal, Quebec. It was a fantastic event, with some

I’ve always been fascinated by crowds — how they form, why they form, what influences them, and what, in turn, they have the ability to influence. I’ve also always tried to differentiate between crowds and communities, the latter being a more “refined” version of a crowd. Communities have purpose, and common bonds that bind the individuals together. So when I came across a couple of choice documentaries recently, that explored the nature, and science, of crowd/community behavior (and what it means as an individual within a crowd or community) the questions started flying. Fast.

I’ve always been fascinated by crowds — how they form, why they form, what influences them, and what, in turn, they have the ability to influence. I’ve also always tried to differentiate between crowds and communities, the latter being a more “refined” version of a crowd. Communities have purpose, and common bonds that bind the individuals together. So when I came across a couple of choice documentaries recently, that explored the nature, and science, of crowd/community behavior (and what it means as an individual within a crowd or community) the questions started flying. Fast.

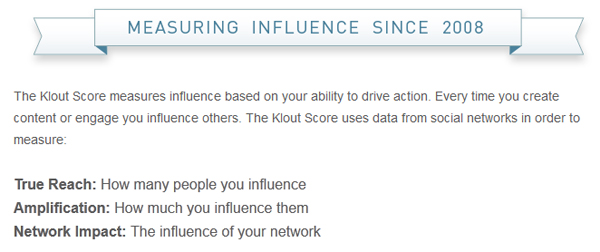

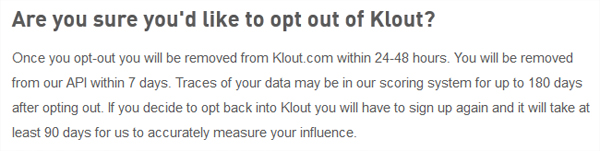

Is it possible to have a Klout Score of Zero (K = 0)?

Is it possible to have a Klout Score of Zero (K = 0)?

Over the years, as an analyst, advisor and even as an entrepreneur, I’ve heard the phrase “Our strategy is to disrupt

Over the years, as an analyst, advisor and even as an entrepreneur, I’ve heard the phrase “Our strategy is to disrupt